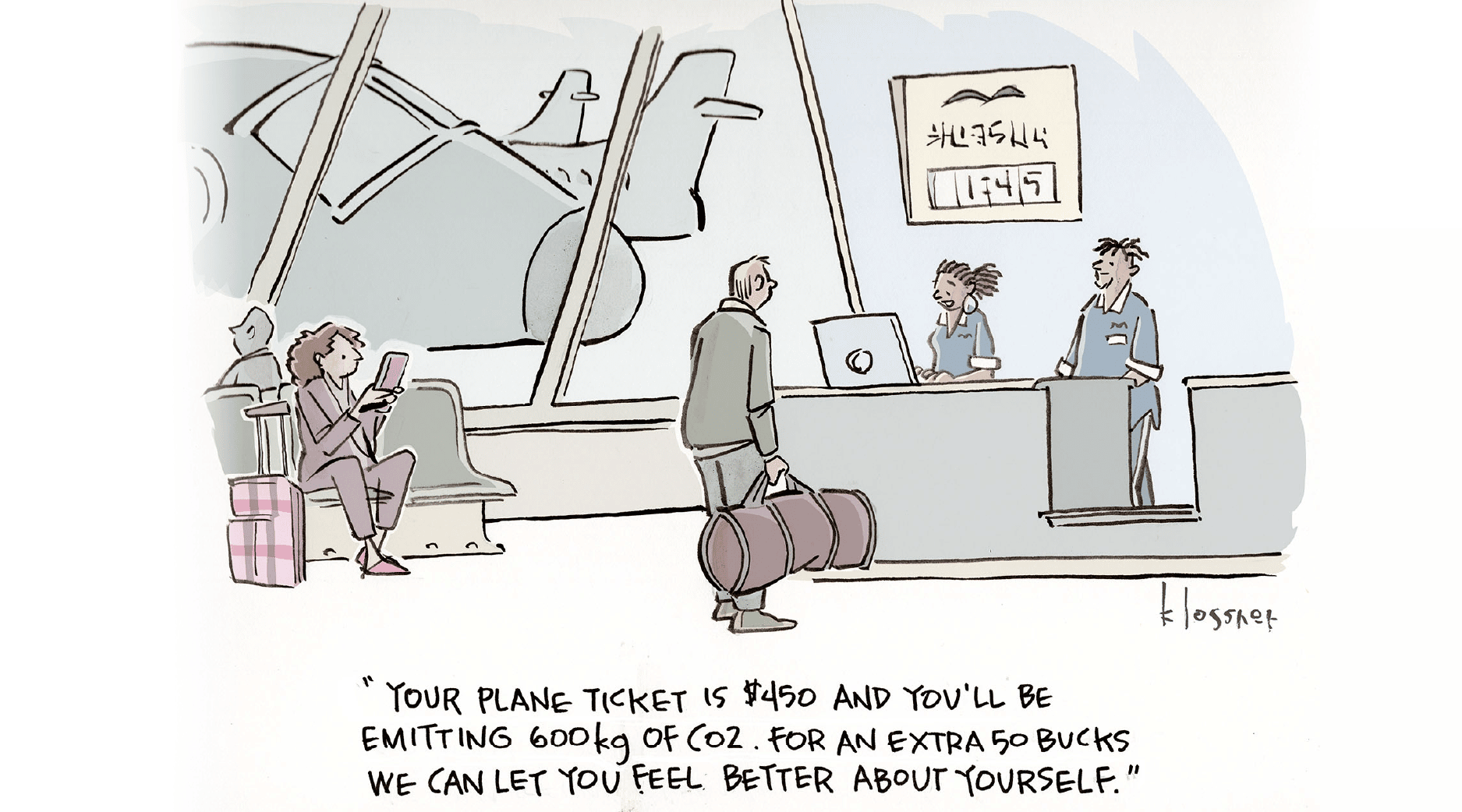

After a grueling couple of years, that summer vacation you kept putting off is right around the corner.

Between thoughts of piña coladas and palm trees, a wave of guilt washes over you—how much environmental damage will that round-trip plane ticket cause?

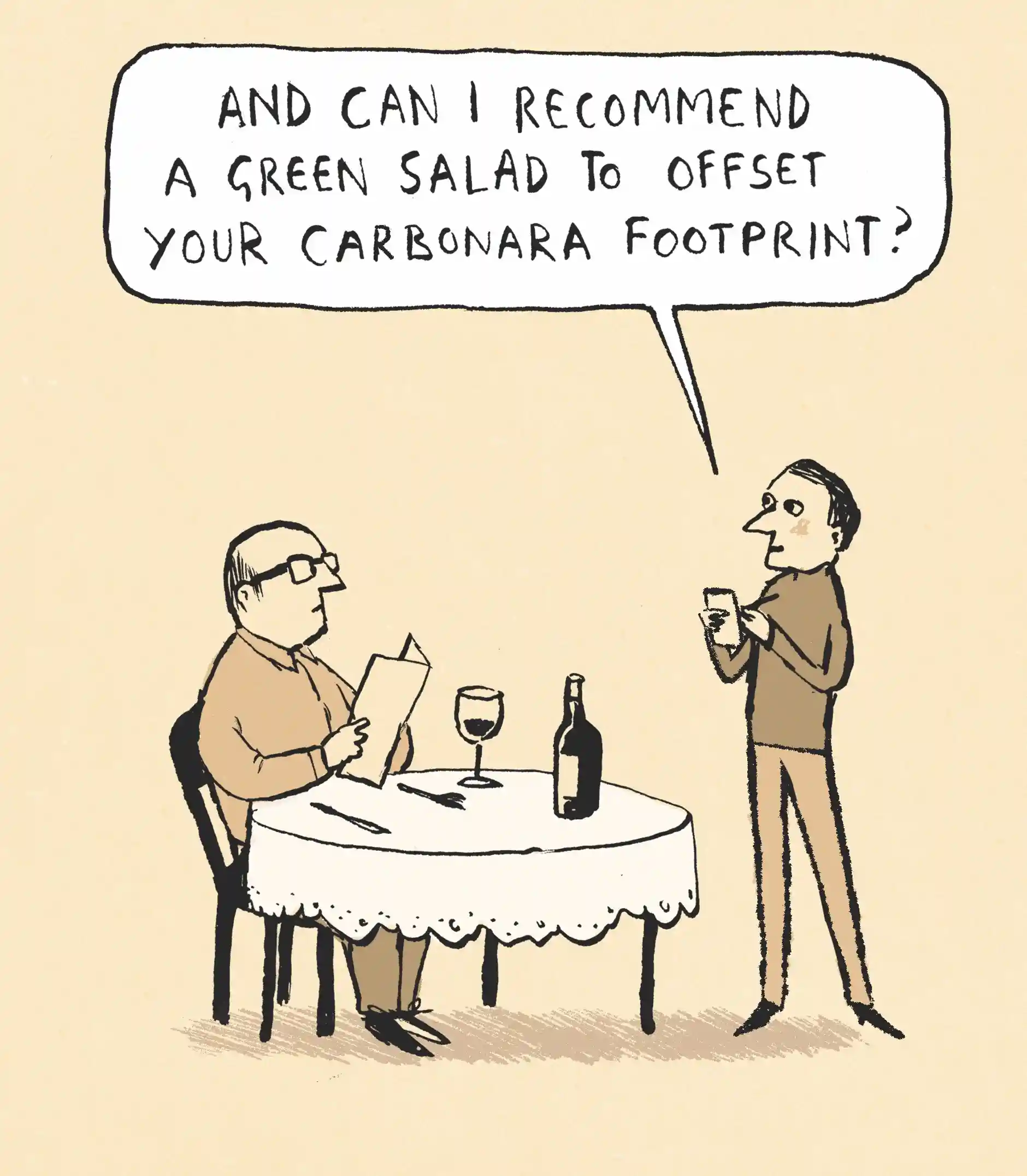

You’re not alone in this thought. Businesses and consumers alike have embraced the carbon offset market in recent years as a way of canceling out environmentally-damaging activities like flying.

The process for buying these offsets as an individual is a breeze—websites like Cool Effect make estimating your planned emissions and purchasing equivalent offsets easier than kicking back on the beach.

But, when you look under the hood, problems with this market start to emerge. Offsets can be greatly exaggerated, allowing companies to greenwash their efforts by claiming “net zero” operations while still producing substantial emissions. In many cases, that money could be better spent elsewhere.

Before we get into the nitty gritty of carbon offset ethics, let’s take a step back to understand how they work.

Carbon Offsets 101

Carbon Offset Guide defines an offset as “a reduction in GHG [greenhouse gas] emissions – or an increase in carbon storage (e.g., through land restoration or the planting of trees) – that is used to compensate for emissions that occur elsewhere.”

It’s as simple as it sounds—your seat on a plane to Cancún represents a percentage of the flight’s total emissions, which is theoretically offset by a carbon-reducing activity initiated from your purchase.

The more emissions you’re responsible for, the more offsets you need to buy. Bill Gates, who racks up emissions jetting around the world, has said that he spends “about $5 million every year to offset [his] family’s carbon footprint.”

While carbon dioxide (CO2) is the most well-known climate change culprit, it isn’t the only pollutant traded in these markets.

Other compounds like methane and chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) also have a warming effect. In order to compare apples to apples, each compound is calculated as a “CO2 equivalent” (CO2e). In simple terms, if a compound has triple the global warming potential (GWP) of carbon dioxide, it would have a CO2e of three.

Methane and CFCs have much more GWP than CO2—so why the incessant focus on carbon?

Mostly, it’s because CO2 makes up the overwhelming majority of GHG emissions. Other compounds have higher GWP, but their concentrations in the atmosphere are far lower.

The point is—emissions offsets are priced in terms of CO2 equivalents, even if CO2 isn’t the compound being offset.

Voluntary vs Cap and Trade Markets

There are two types of carbon offset markets—voluntary and cap and trade. When you’re thinking about purchasing credits to offset vacation emissions, you’re in the former camp. Just as it sounds – voluntary means that individuals and companies are proactively opting into choosing to offset their emissions debt. This practice can be both altruistic and a form of greenwashing by some companies looking to gain public goodwill.

Cap and trade works a bit differently. In order to incentivize emissions-reducing innovations, governments allot a total number of metric tons of CO2e that each company within an industry is allowed to emit each year. Companies that stay under this cap can sell their excess emissions capacity to others whose operations put them over the limit.

With each passing year, the cap gets lower and lower until it eventually hits zero. The idea is that this scheme gives companies time to adjust their operations to a net-zero world, with innovative companies being rewarded in the meantime. Cap and trade is a mandatory policy lever that more than a dozen U.S. states participate in to meet their climate goals.

And some companies, like Tesla (ever heard of it?), have cashed in.

In the first quarter of 2021, Tesla generated an eye-popping $518 million in emissions credit revenue, representing nearly all of its profit for the quarter. As an automaker, the company receives credits that it doesn’t use, since it exclusively produces electric vehicles (EVs). It sells those credits to combustion-engine producers that need more than their allotted share to stay under the cap.

This all sounds good on paper. Tesla is doing the environment a favor by mass-producing EVs, and is rewarded with a double advantage—its competitors lose money from purchasing credits, and that cash goes directly into Tesla’s pocket. I imagine there’ve been many curse words directed towards Elon in Detroit boardrooms.

So, what’s the issue?

While offsets may work relatively well in the auto market, credits sold from other sources—especially protected forests—are more dubious.

Not all credits are created equal

Many assert that offsets have rightly hastened the transition to an EV future. But the question becomes thornier when offsets in the form of forest protections are sold.

Municipalities across the U.S. have their eye on the pot of money offsets represent. Michigan has already gotten into the game.

The state anticipates generating 10 million credits via forest protections over the next decade, creating a windfall for its government. The problem is, its forest managers don’t expect any change in how the land is managed as a result of the credits. There will be no reduction in timber harvesting and no increase in protected areas.

So, if management of the forests isn’t changing as a result of the credits sold, have the credits actually done anything to reduce GHG emissions?

Welcome to the problem of additionality. An offset is considered ‘additional’ if its purchase creates an environmental benefit that wouldn’t have existed otherwise. So, credits sold in the name of protecting a forest that’s already protected wouldn’t meet this criterion. States like Michigan assert that, in the absence of the revenue generated from selling offsets, timber harvests would drastically increase. Upon closer examination, this claim seems suspicious.

Forest management is a delicate exercise. Competing interests such as ecological protection, timber harvesting, recreation, and wildfire management all need to be balanced, and it isn’t easy to drastically increase or reduce harvesting quotas without knock-on effects.

And additionality isn’t the only cause for concern. Permanence is the second pillar of a high-quality carbon credit—it refers to the likelihood that the offset-induced carbon reductions will last forever, or at least a really long time.

In the case of forests, this is a precarious assertion. Just last year, the Bootleg Fire in Oregon burned nearly 400,000 acres, wiping out a fifth of forests set aside for offsets. Purchasers of those offsets were promised a one-hundred-year survival.

With the majority of carbon offsets in the U.S. being designated as “Improved Forest Management,” additionality and permanence concerns cast doubt on the future of the market.

Keep it local for a greater impact

If it’s not clear by now, the carbon offset market has a long way to go to become sufficiently transparent and reliable. It’s a good concept, but needs more robust enforcement.

In the meantime, there are better ways to reduce your footprint rather than purchasing carbon offsets:

- Instead of flying, take a train to your destination, if possible. Travel by train cuts your carbon footprint in half versus flying. (Author’s note: The problem is, there aren’t many trains to island destinations).

- Better yet, calculate the cost of offsetting your emissions using a calculator like Cool Effect. Once you have a total cost, donate that money to a local environmental initiative. This way, you can actually see a tangible climate benefit from your cash.

- Put that money towards savings for an EV or solar panel for your house. Switching to renewable energy sources is one of the most high-impact behaviors individuals can take to battle climate change.

This is all to say that navigating the carbon offset market is murky right now. But, there are a number of nonprofit groups, businesses, and individuals working to make it clearer for the millions of altruistic individuals and companies that want to make good on their intentions for the planet. Funding climate mitigation projects thousands of miles away may make sense for some companies making large offset purchases. In the meantime, individuals can make the biggest difference to minimize their carbon footprint through local choices made every day about where to eat, what to buy, or the types of transportation to use.

By keeping your climate impact local, you can inspire others and see a tangible benefit from your actions. Until carbon offset markets have matured, this is your best bet for minimizing your carbon footprint and inspiring action in others.