Regardless of the final outcome of the mid-term elections, there are concrete steps that you, individually, can choose to take right now for clean energy progress.

In The Big Fix: 7 Practical Steps to Save Our Planet, co-authors Hal Harvey and Justin Gillis lay out how and why individuals can make a big impact. In this week’s issue, Gen180 Executive Director Wendy Philleo interviewed Hal–a leading strategist in the nonprofit sector’s efforts to reduce the impacts of climate change–on what he hopes readers take away from the book.

The following interview has been edited for clarity and length. See the full video interview here.

Wendy Philleo: All right. Well, welcome Hal Harvey, good to see you again. Thanks for taking the time to talk with me about your new book, which I have here, The Big Fix: 7 Practical Steps to Save Our Planet that you wrote with Justin Gillis.

Hal Harvey: Thank you. It’s a delight to be here. And I really appreciate the chance for this conversation.

WP: Great. Can you share a little bit about your background and a little bit about why you came to this decision to write this book. Why now?

HH: Sure thing, I’m an engineer by training with degrees in both civil and mechanical engineering. I got involved in the energy business when I turned 18, because I was obligated to go register for the draft, because Jimmy Carter reinstated it in order to build the so-called Rapid Deployment Force in the Mideast, which was aimed at protecting American interests against foreign oil producers. And so that put a pretty sharp focus on the question of oil and oil imports. What I was doing at the time was home construction solar homes with my brother. And we came to realize that it was not very complicated or difficult to build a solar heated home.

And to have this dissonance on the one hand between getting ready to go to war, not so long after the Vietnam War wound up in its tragic way – and on the other hand, having readily available technologies to save energy. And this was at the time when cars got an average of 13 miles per gallon. So we weren’t just importing [oil] we were wasting it in just copious quantities, we still are.

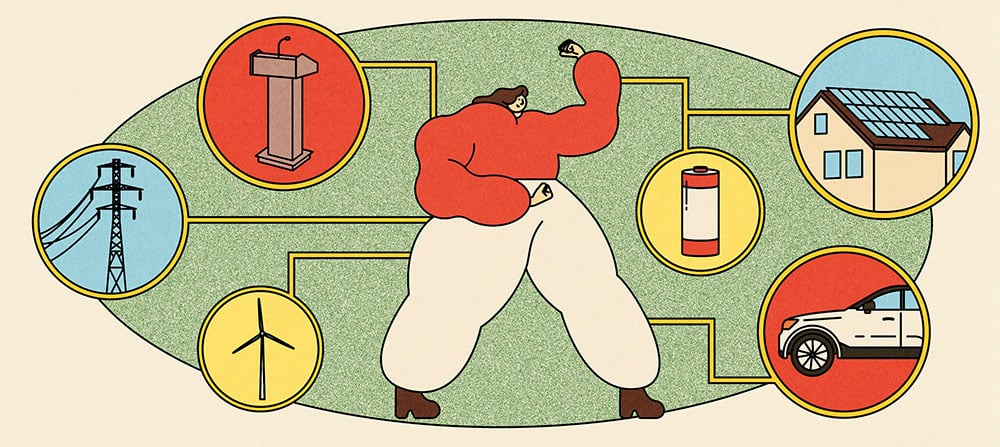

WP: Your book felt like almost a call out for a revitalization or renewal of civic engagement, in a way, because you talk a lot about citizens flexing their muscle, exercising influence and finding these levers – sometimes secret levers, because people don’t know about them. Can you talk a little bit about a few actions that you think are most important for people to know about?

HH: So this is the right question, because what motivated us to write the book is to identify the places where citizen actions can make a big difference. I mean, the normal reaction to a political issue that you care about is to write a letter to your Congressperson. That turns out not to be the most effective thing to do. Civic engagement is wonderful, but if you know who makes the decision that most affects the planet, then you can make a strategy for changing that decision.

And that’s what the book is all about. When you send in your utility bill at the end of the month, does that money land on green choices or dirty choices? Who decides whether your money goes to solar and wind or coal and natural gas? And the answer is the Public Utility Commission (PUC) of your state. How many people have stood before their state’s Public Utilities Commission and said, ‘Hey, let’s get this straight. We need to quit cooking the earth.’ How hard is that? And how complicated is it? And what happened? So we tell in this book, not only how to identify those levers of power, but stories about how people got involved and pulled those levers that made a big difference.

WP: Just how many Public Utility Commission Commissioners are there in the U.S.?

HH: Just over 200. So roughly five per state. These people control 40% of the carbon emissions in our economy. That’s amazing. That’s a big number, and those 200 people are obligated to listen to you. They’re called Public Utilities Commission’s because they’re supposed to serve the public. They have hearings and you can stand in front of them and make your point. Now, a lot of the conversation at these meetings is a sort of a regulatory patois between utility lawyers and PUC lawyers. And that requires lots of specialized knowledge.

But let’s say you live downwind of a big coal-fired power plant and your kid has asthma. The PUC is obligated to listen to you and your kid. You can tell them what it’s like to be a mom to have a kid who can’t breathe, and that it’s the PUC’s responsibility for that, and therefore it’s on them to change. You know, the climate change picture is pretty horrifying if you study it closely. My suggestion is people should study it enough to get concerned, but then flip to the solutions as fast as possible.

“People should study it enough to get concerned, but then flip to the solutions as fast as possible.”

Because that’s enabling. It’s energizing as well. And when you focus on solutions, your strategy becomes much more pointed than just raising awareness. It turns into how do I save this planet? How do we keep it from just burning right up?

WP: I think the problem with energy issues is that it feels complicated, and it feels like it should be left to the experts. Right? So what do I know about building codes? Or what do I know about utilities? I do feel like there are barriers around this type of engagement—how does the average person get comfortable doing this?

HH: Well, it’s good to have some logic, I would recommend a couple of days study before working to intervene in one of these decision-making venues. It’s also a great idea to look and see who else is doing this work in your region and if you can piggyback onto them.

Every good argument has ethos, logos, and pathos. So ethos, this is your ethical standing. Every single National Academy of Sciences scientist has argued for rapid action on climate change. You don’t have to be that scientist, but it’s totally legitimate to point out that they are all saying it, there’s your ethos. Your logos, it’s now cheaper to build a solar farm from scratch than to just pay the operating costs of a coal-fired power plant. It’s amazing. Again, you don’t have to fight every detail there. And pathos – how does it make you feel when your kid has asthma or when soot is sitting on your windowsill at the end of every single day? So take those elements, put them in human terms and present them. It turns out, that’s a very hard combination to defeat.

WP: Love that. That’s very empowering. How has the Biden-Harris Administration’s efforts and the passage of the Inflation Reduction Act changed the equation for you in terms of the recommendations that are in this book?

HH: We wrote the book before that all happened. So the question is, do those recommendations survive? And it turns out, they not only survive, they thrive. We argued for rapid decarbonization of the electric grid by switching from fossil fuels to renewable fuels. Well, the IRA just made that even easier because economics is now a tailwind instead of a headwind. So across the board, I think it accelerates and emphasizes the suggestions in the book. We have reached an interesting point in the energy economy of the world – it’s now cheaper, I often say, to save the world than to destroy it.

“It’s now cheaper, I often say, to save the world than to destroy it.”

WP: I think one of the things that’s frustrating is knowing that renewable energy is popular across the ideological spectrum – that most (70%) of Americans support climate action. It’s actually a more popular issue than people realize. How do you deal with the disconnect in how people see momentum at the state and federal levels?

HH: Well, to some extent, the waters have been purposefully poisoned by people who resist change. I mean, if you look at the Koch brothers who have made close to hundreds of billions of dollars in the oil and gas business, and then you look at their political contributions, the answer becomes sort of glaringly obvious in some cases. But we also have some responsibility ourselves to think about civic action and how to overcome this. It’s often counterproductive to talk about climate change, instead of clean energy, because the numbers for clean energy are even higher than for climate change, regardless of the fact that they’re the same thing. Start with interests, bring in local examples, and identify those secret levels of power – there’s still powerful economic interests that will fight this, and we can’t win by being too precious.

WP: I thought it was really interesting at the end of your book that you added a chapter around religion. That was a surprise to me, and I thought it was really interesting. Can you talk a little bit about why you added that and more broadly about what role you think culture needs to play in terms of speeding up this transition?

HH: You know, there’s a great moral question hanging over all of this, which is, do we have the right, as citizens of today, to leave behind burnt offerings for citizens of tomorrow?

“There’s a great moral question hanging over all of this, which is, do we have the right, as citizens of today, to leave behind burnt offerings for citizens of tomorrow?”

Do we have the right to destroy the topsoil, to alter the weather patterns to extinguish life in the oceans, to let mighty forests burn, to flood out entire towns? More than half of Pakistan was underwater this year, in terms of the population. So I don’t think we have that right. I don’t think we have the right to cheat future generations for our near-term. And I don’t think we have to. We have to make some hard choices. Avoid doing that. So from my perspective, it is an ethical question, not a religious one. I’m not a religious person. But I hope I’m an ethical person – I try to be on a good day. And that’s where the question arises, you know, what is our obligation?

WP: And from a broader cultural perspective, what do you feel needs to happen on that front? It feels like a real shift needs to take place in terms of speeding up the rate that we need to act.

HH: You know, we need to first of all be optimistic about the future, rather than harp on problems. A little bit of optimism goes a long way. I had a friend who said optimism is a social change strategy.

“Optimism is a social change strategy.”

And he’s right. That’s one thing we have to do – ‘pull up your socks’, as they say, in England, go get something done.

WP: I think that’s part of the challenge, right? Like how do we make building codes, heat pumps, you know, Public Utility Commissions sexy so people think about these issues? It’s not an easy thing, but I think there’s a way to do that and starting with the solutions and the optimism and reaching people in different ways is really important. I’m glad to hear that you feel optimistic and that we’re up to the task. If there is one takeaway that you want to leave people with, what is it?

HH: There’s a lot you can do. It seems like a big intractable problem, but there are opportunities in every corner. In order to find those opportunities, you have to know something – not a lot – but something about the energy system in which decisions are the most critical, who makes those decisions, and how you can intervene in those decisions. It takes a couple of days of homework. It pays to look for groups that are similarly strategic in your region, and then jump in without fear. Right? If we have an ethical duty and great opportunity to quit poisoning our children, let’s do that.

WP: And take advantage of this opportunity of innovation and economic gain as well.

HH: Yes, exactly. It’s all right there in front of us.

WP: Well, thank you for taking the time. I really appreciate it.

HH: Thank you Wendy, really delighted to have this chance to catch up.