Matthew McFadden was born and raised in Wise County in southwestern Virginia’s coal country. In the mid-2000s, McFadden was working in sales at a local electronics company, while several members of his family worked as miners in underground coal mines. “I saw what my brother-in-law and my father-in-law were bringing in monetarily and explored that [profession],” McFadden said.

It seemed like a natural career path for someone who grew up in a coalfield region. “It’s part of who we are,” McFadden said. Eventually, McFadden completed his training certification in underground mining.

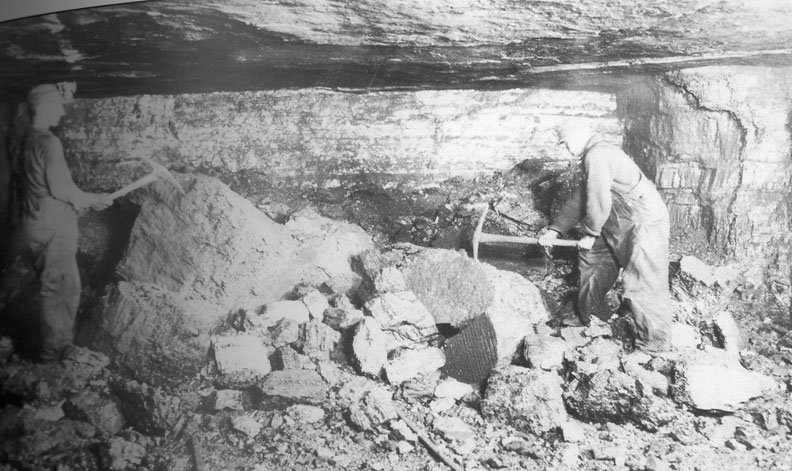

-

Coal mining in Wise County dates back more than a century. Photo: Virginia Coal Heritage Trail.

As luck would have it, on the day he went to meet a mine foreman for a potential job, he got lost; McFadden didn’t connect with him. He went to his father-in-law’s house afterward and as they sat on the porch, the two men had a heart-to-heart conversation. “He urged me not to pursue underground mining,” McFadden said.

McFadden’s father-in-law had more than 30 years of experience working as an underground coal miner. He lived through the industry’s boom in the 1970s and its bust in the 1980s when demand for coal from Appalachian mines declined significantly. Factors that contributed to that decline included clean air regulations, competition with other fossil fuels, and technological advances that replaced workers with machines.

-

In some ways, a coal miner’s job is not too dissimilar to what their great-grandparents would have done, such as shovel coal deep underground. Photo: Spencer Platt, Getty.

“My father-in-law is a hero of mine,” McFadden said. “He loved what he did… He had fun down there with all the folks he knew, and [he] knew he was providing a good and honest life for his family. Being a life-long miner was something he was really proud of.”

His father-in-law was frank, too, about the toll underground mining takes on the body and the danger of the work itself. “He said he didn’t want his daughter to have to worry every day – like her mom did – about whether I would come home or not.”

“He said he didn’t want his daughter to have to worry every day – like her mom did – about whether I would come home or not”

McFadden’s father-in-law isn’t wrong—Coal mining is a dangerous business. Even with the precipitous decline of coal use in America, seven fatalities have already occured this year, as of the writing of this article. The CDC and the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health have known for decades about the cancerous effects of the carcinogens in coal mine dust that miners breathe while underground. All the while some coal companies have been found incorrectly denying miner’s medical claims from working in these dangerous conditions.

McFadden heeded his father-in-law’s advice. He continued to pursue a career in consumer electronics as a project and training manager. But this work moved him away from home to jobs in Charlottesville and Richmond.

McFadden wasn’t the only one moving away from the region either. The coal mining activity in southwestern Virginia continued to decline through the Great Recession of 2008 and beyond. McFadden said many miners attribute those job losses to the Obama Administration’s Clean Power Plan. Coal jobs that went away never came back.

In part, the health and safety standards that the Clean Power Plan introduced made coal more expensive to produce, and in turn, it began to lose market share. A 2015 report by the Economic Policy Institute anticipated that gross job losses as a result of the Clean Power Plan likely would be geographically concentrated, “raising the challenge of ensuring a fair transition for workers in sectors likely to contract due to the CPP.”

While the Clean Power Plan made coal more expensive, coal consumption had been declining from its peak since 2000 across the country, 15 years before the Clean Power Plan was introduced. Since its peak decline in 2007 through 2013, coal-fired electricity generation fell 25 percent. Coal was unable to compete with cheaper energy sources, namely natural gas produced by fracking.

“So people moved or they had to try to retrain on something else,” McFadden said. Most of the time, “they weren’t making anywhere near what they were making before. So it was quite a large life adjustment for a lot of these folks and for the towns and businesses.”

Making a living in different cities didn’t feel right for McFadden. He wished the money he was earning could’ve gone back to help his hometown, where he wanted to raise his daughter.

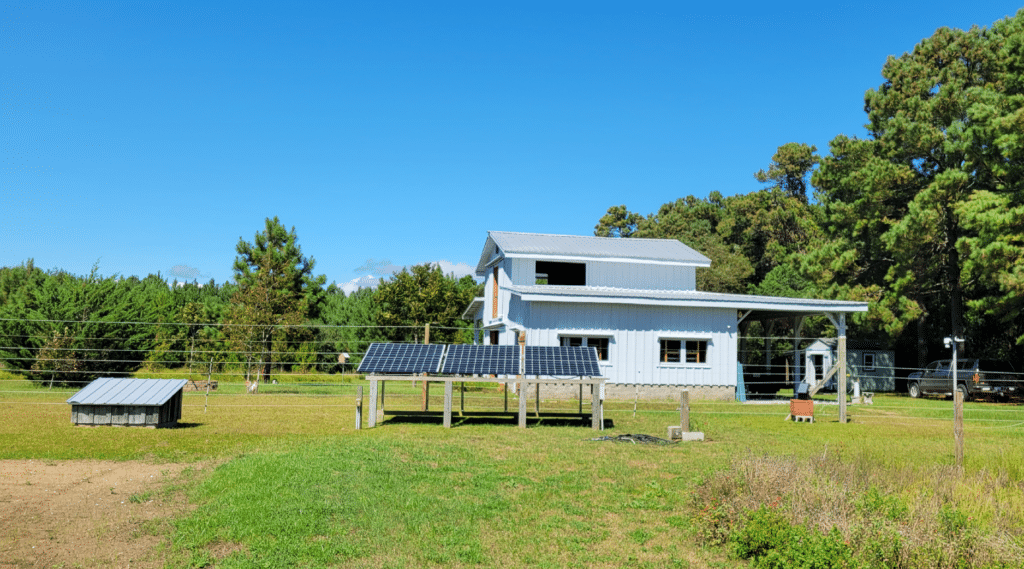

When he looked into returning home, McFadden learned about up and coming jobs in renewable energy. He found a job with a company that makes commercial-scale solar energy affordable to schools, hospitals, businesses and local governments in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeast regions.

-

Solar panels on roof of Duffield Regional Jail in Southwest Virginia, near Wise County. Photo: Christine Gyovai.

McFadden loves to work for a company that’s creating jobs with livable wages that support families and encourage young people to stay in town.

“These aren’t just flash-in-the-pan jobs,” he said. “These are going to be jobs that people are going to be able to make careers out of by building these systems, operating and maintaining them.”

Renewable energy companies working in the region along with his are also working with community colleges to help create internships and training programs. They’re employing long-time skilled professionals, like electricians and construction workers. He thinks the region is well suited to continue its legacy as an energy producer.

“Why not take advantage of what we’ve done in the past?” he said. “We’ve got areas that have been stripmined where the land is useless. We can take that land and put something that makes somebody’s house light up… that powers their computer. Whatever it is, we can still be an energy powerhouse.”

Creating a livable and brighter future for his daughter also motivates his work in solar energy. “Climate change is real,” he said, “and we need to make the world a better place for not only our children but also our great, great grandchildren… so that the world is not 100 degrees on average and the ice caps aren’t melted.”

“Climate change is real, and we need to make the world a better place for not only our children but also our great, great grandchildren”

His company will soon install solar panels at his 9-year-old daughter’s school. McFadden’s face lights up at the thought of his little girl looking up at the solar panels at her school. He knows his daughter will feel proud and “know that her dad helped make it happen.”