This post was written by Matt Turner, Creative Manager at Generation180

When we got our first electric vehicle (a used 2016 Volkswagen e-Golf) two years ago, my family, friends, and neighbors became curious. Many began asking me if they should buy an EV. Now, as EVs have quickly become more mainstream and the number of available models has skyrocketed, the question changed from if they should buy an EV to when? Is the price at the right point now, or should I wait a couple of years? Are there enough models to choose from that fit my lifestyle? Is it hard to find a place to charge?

Maybe you have a traditional internal combustion engine (ICE) car that works fine…for now. But within a year or two, maybe you expect to be needing a new (or new to you) car. Should it be an EV? Does it make sense to swap my ICE car a little early to begin saving money now? When do I pull (or plug in) the plug?

In this post, I share my decision-making process — one you can follow to help you make the right decision at the right time that makes sense for you. Buying any vehicle is a big decision with lots of variables and nuance, but hopefully, I can help you get pretty close.

For the sake of simplicity, whenever I mention an EV, I will only be discussing Battery Electric Vehicles (BEVs) and not Plug-In Hybrid Electric Vehicles (PHEVs), unless I specifically call them out.

After studying the many questions Generation180 gets around EVs, and from lots of personal conversations I’ve had, it seems to me that there are two main determining factors to see if now is the time to buy an EV:

1. Practicality: Can I do the same things with an EV that I usually do with my ICE vehicle?

2. Cost: Can I afford the initial cost, and will I save money compared to an ICE vehicle?

Note: each section contains a “short answer” and a “long answer”. If the short answer gives you all you need, feel free to move on. Or if you want a little more detail, check out the long answer. Each section has a “the bottom line” at the end to give a quick summary.

Practicality:

The fact of the matter is: EVs are cars just like traditional ICE vehicles, but with a different (and better) way of moving from place to place. Manufacturers know what Americans’ needs are, and they are meeting them. It seems most EV models coming out are mid-sized SUVs, and a mid-sized SUV just so happens to be the best-selling non-truck vehicle in America so far this year.

Range

The second most popular question I get about EVs is “What’s the range?”—we’ll get to the most popular one later.

The short answer:

It’s probably more range than you need. The average driver drives only 39 miles round trip per day. Considering there isn’t a single new battery electric vehicle available that has less than 110 miles of range (and the majority have more than 250), it’s safe to say no matter what new EV you get, most people will have enough range to do their daily driving.

The long answer:

The average range doesn’t work for everyone, so let’s discuss some more specifics. Especially in rural areas, the miles driven are higher. In states like Wyoming, the average daily drive is the highest in the nation at 65 miles per day. However, even the smallest range EV will have nearly double the needed range.

What about long-distance commuters? There are at least 26 BEV models available in the U.S. right now, and 22 of them have more than 200 miles of range standard, and they offer as high a range as more than 400.

The bottom line:

If your daily commute is within 200 miles roundtrip, it’s very easy to find an EV that has enough range as your daily driver without the need to charge during trips.

Charging

Speaking of charging, it goes hand in hand with the range conversation. Most EV owners charge at home (81% at home, 7% at work, and the rest at public chargers). Think of charging your EV as you charge your phone. By and large, most of us charge our phones at home overnight, but at times you may want to plug it in somewhere away from the house. EV charging is like that. So what does charging look like with an EV?

The short answer:

Just like there are three main types of gasoline available at the pump, there are three main types of charging available for EVs. Level 1, Level 2, and Level 3 (being the fastest). Charging at home is either Level 1—plugging into a standard wall outlet—and gets you 4-5 miles per hour, or Level 2—think of a dryer or stove plug—and gets you 25-75 miles per hour. Level 3 chargers are usually the ones you see out in public and can get you as fast as 180-300 miles per hour depending on the charger and the car.

The long answer:

Level 1 charging is the cheapest way to get started charging your EV. Every car comes with a cord that you plug directly into any standard wall outlet in your home. While slow, it still covers what most people drive on a daily basis. For example: if you drive 30 miles per day, plug in your car when getting home at 6:00 PM, and unplug it when you leave for the day at 7:00 AM, you still charge at least 44 miles.

Most Level 2 chargers can be installed in your home for around $1,200. This price can be reduced as many states and localities offer hundreds of dollars in rebates when installing. The convenience of being able to more quickly charge your car can make this install worth it. Many Level 2 chargers also have capabilities for more advanced charging schedules and energy monitoring to see how much money it’s costing to fill up. While I used a standard Level 1 charger for my EV for months without issue, I highly recommend getting a Level 2 charger installed if possible.

Both Level 2 and Level 3 chargers are usually what you will see in public charging areas. Some of these are free, and some cost money to use. There are a number of different companies that offer the services, and you usually need to download an app to your phone to use the chargers. Like gasoline prices, the cost to use varies depending on location and service provider. The one thing you can count on is that if the charger isn’t free, then it will likely cost more to charge at a public station than at your home.

One nice thing about charging stations around town is they are often installed at places your car will be parked at for some time like shopping centers, restaurants, and grocery stores. While on road trips you can find charging stations at popular hotels to charge overnight, at national parks, and more and more, large gas stations are installing EV chargers. Both Apple Maps and Google Maps show electric vehicle charging stations within their route planning, and there is a growing movement of smart planning options to help you find charging stations while you stop for lunch or to stretch your legs.

The bottom line:

You’ll do the vast majority of your charging at home, which is more convenient than having to go to the gas station. If you do need to charge, the network is large and growing, and there are tons of resources to make it easier.

Model availability

So now you’re thinking “All of the above is fine and dandy, Matt, but are there any EV models that actually do what I need them to? I have kids, a dog, and we go mountain biking on weekends an hour away. Is there an EV that lets me do that?”

The short answer:

Probably. Check out the list of currently available models to find the features you need. But most EVs available today are SUVs with hundreds of miles of range. I personally know a few families who fit the above description and love their EV. I have three kids myself, and we love our EV too.

The long answer:

Probably. When thinking about what car to purchase, it’s important to think about needs. What do you most need your car to do? Many EV households still maintain one gasoline-powered vehicle and drive their EV 70% of the time. This is probably the most difficult question to answer as every person’s lifestyle has its own unique needs. To help illustrate the potential of EVs, I’ll lay out a few lifestyle examples below.

Frugal local commuter. I live really close to my work, grocery store, and favorite restaurants. I probably drive 10 miles a day and love to take my dog to the local dog park and enjoy my city. On the weekends I might go to the next town over to visit a friend or family member.

What EV works for me? Basically any of them. If this describes something close to your life then your only real decision is what style you like and what your price point is.

Outdoorsy couple: The local commute isn’t what concerns us, we need to make sure our car can get us an hour out of town and back with a trunk full of camping gear and our mountain bikes in tow.

What EV works for me? More and more every day. Look at the Hyundai Kona EV, Volkswagen ID.4, and the Ford Mustang Mach-E. These have hundreds of miles of range, roof racks and trailer hitches for equipment, and space in the trunk for more gear.

Family with 3 kids: It’s not camping gear I’m hauling, it’s three kids in car seats. Please tell me there is an EV with a third row!

What EV works for me? The Chrysler Pacifica PHEV, Tesla Model Y, and Tesla Model X. Third-row EVs are currently limited but still available, and next year and the following, a slew of third-row EVs will hit the market.

Personally, my family has three kids, all in car seats, and we do 80% of our driving in a 2016 Volkswagen e-Golf that has 85 miles of range. It’s not uncommon for the five of us to go to the grocery store and still fit an overflowing diaper bag and a trunk full of groceries comfortably enough. When you weigh in what you actually need from a vehicle, often you come to different conclusions than what the manufacturers are trying to upsell you.

The bottom line:

Especially in two-car households, there is an EV model that fits just about everyone’s needs. List out your needs and see how an EV can fill them.

Bonus: Lifetime emissions

This question is one I hear a lot. Given the materials needed to manufacture electric vehicle components, and the fact that many electrical grids in America are still majoritively powered by natural gas, do EVs actually have a lower carbon footprint?

I won’t get into a “long answer” here as this topic warrants its own article. But the short answer is: yes. From cradle to grave, electric vehicles are better for the environment than conventional cars everywhere.

Three separate, independent, high-quality studies have shown that even if you take into consideration all lifecycle stages of an EV, including vehicle production (extraction of raw materials, processing, assembly, painting, etc.), vehicle use (driving, charging, maintenance, etc.), and end-of-life (re-use, recycling, disposal to landfills, etc.), electric vehicles, hands down, are better for the environment and produce far fewer emissions than ICE vehicles.

Cost

When we discuss costs, it’s helpful to think in terms of the total cost of ownership over time. That just means that over the course of the time that I will own the car, will it cost me more, or less money than a comparable ICE vehicle would’ve cost me.

To figure this out, let’s start with the initial investment. The fact is that many EVs have an initial sticker price that is higher than a comparable ICE vehicle—which is a big deal for most of us. For example, the most popular non-truck vehicle of 2021 so far is the Toyota RAV4 which has a starting price of $26,350. A comparable EV is the Hyundai Kona Electric which has a starting price of $34,000. That’s a $7,650 price difference.

But those numbers are a bit deceiving when we think about the total cost of ownership. Overall, you will spend less money when owning an EV than an ICE vehicle. Let’s dive into why.

Tax incentives

The short answer:

Most new EVs on the market today qualify for a federal tax credit of up to $7,500. This generally brings the cost of a new EV in line with a traditional ICE vehicle.

The long answer:

Once you file your taxes, you can use the $7,500 federal tax credit towards reducing your tax bill. In the above examples I gave, this immediately brings the EV and ICE vehicles to an almost identical price point. And even better, it looks like that tax incentive may be increased up to $12,500 next year, which would put those EVs at around $4,500 less than their ICE counterparts.

On top of federal incentives, take a look at state incentives for EVs where you live. Some states like California and New York offer grants and rebates from $500-$5000 depending on the model. As more and more states adopt friendlier EV policies, we should see more states adopt more incentives.

The bottom line: tax incentives often bring the upfront cost of an EV to a similar (or cheaper) price point as an ICE car.

Filling Up

This is by far the most common question I get: “How much does it cost to charge?” Just like with ICE vehicles, this varies depending on the model, how much you drive, and how much you pay for electricity.

The short answer:

One simple way to suss this out is to compare the cost of a gallon of gasoline to a similar amount of energy you get from electricity (called an e-gallon). In Virginia, I spend about $1.00 per “e-gallon” at the time of this article. Compare that to the gas station near my house which is currently selling gasoline at $3.19 per gallon—more than three times as much.

That’s a very generalized figure, and it varies from state to state, but feel free to try it out here. If that number is as detailed as you need, skip down to the next section. But if you’re interested in figuring out exactly how much driving an EV would cost/save you, I’ll lay out a (hopefully) simple illustration here.

The long answer:

To compare appropriately, I’ll use the two vehicles I mentioned earlier, and some current US averages on gas and electricity costs. I’m also assuming you’re charging at home like the vast majority of EV owners do.

U.S. Average miles driven per year: 14,263

2021 Toyota RAV4 efficiency: 30mpg

U.S. Average price per gallon of gasoline: $3.29

2021 Hyundai Kona EV efficiency: 2.7 kilowatthours (kWh)/mile

U.S. Average price per kilowatthour (kWh): $0.14

ICE Driver: I drive my Toyota RAV4 14,263 miles per year and get 30 miles per gallon. It costs me $3.29 per gallon of gasoline, and so I spend $1,564.18 on gasoline for the year. (14,263/30) * 3.29 = $1,564.18

EV Driver: I drive my Hyundai Kona EV 14,263 miles per year and use 2.7 kWh of electricity per mile driven. It costs me $.14 cents per kWh, and so I spend $739.56 on electricity for the year. That’s more than 50% cheaper than driving an ICE vehicle. (14,263/2.7) * 0.14 = $739.56

This equation gets even better if your utility has a time-of-use rate that lets you pay cheaper rates when charging on non-peak times. For example, I schedule my electric car to charge from 12:00 AM to 5:00 AM when electricity is only 7.3 cents per kWh. Meaning driving 14,263 miles only costs me $359.03 compared to more than $1,500 in one of the most fuel-efficient ICE vehicles on the market.

The bottom line:

EVs are far cheaper to drive on a daily basis; conservatively ½ as much and as little as a ¼ as much.

Maintenance

Let’s move on to normal wear and tear costs. You may know that EVs have far fewer moving parts than ICE vehicles, which is a great thing when it comes to maintenance costs (a Chevy Bolt, for example, has 80% fewer moving parts than a comparable ICE vehicle). More moving parts means more wear and tear. EVs also have no exhaust system, less need for cooling, less wear on braking, and no need for oil changes, fan belts, timing belts, head gaskets, spark plugs, etc. The list goes on.

The short answer:

EVs can save owners $4,600 in maintenance costs over the life of the vehicle. In general, most of the more expensive repairs for cars happen at around the 5-year-mark, so that’s where you will really begin to avoid potential repair costs.

The long answer:

There aren’t zero repair costs for an EV, of course. Like an ICE vehicle, you still have a heating and air conditioning system, tires, and suspension components, but those are the same to maintain as an ICE vehicle.

There are two main things an EV has that an ICE vehicle doesn’t: an electric motor and a large battery. How much do they cost to repair? The good news is that while an electric motor is expensive to fully replace ($6k-$9k), it almost always outlasts the life of the vehicle and lasts much longer than a traditional internal combustion engine. It’s not something you’ll need to worry about.

Replacing an EV battery outright could cost you $5,500 (about the same price as replacing an engine in a midrange gasoline vehicle). EV battery warranties are as generous as eight years and 100,000 miles. Even if there was an issue with the battery, they don’t usually need to be fully replaced. Unlike gasoline engines that can unexpectedly blow a gasket and leave you stranded on the side of the road, an EV battery simply degrades over time. So after 10 years, your EV’s range may be reduced from say, 300 miles to 270 miles — still more than most people will need on a daily basis.

The bottom line:

Over the course of the vehicle’s life, EVs can cost $,4600 less to maintain. Even if you don’t own the vehicle that long, it still costs less to maintain than an ICE vehicle.

Next Steps:

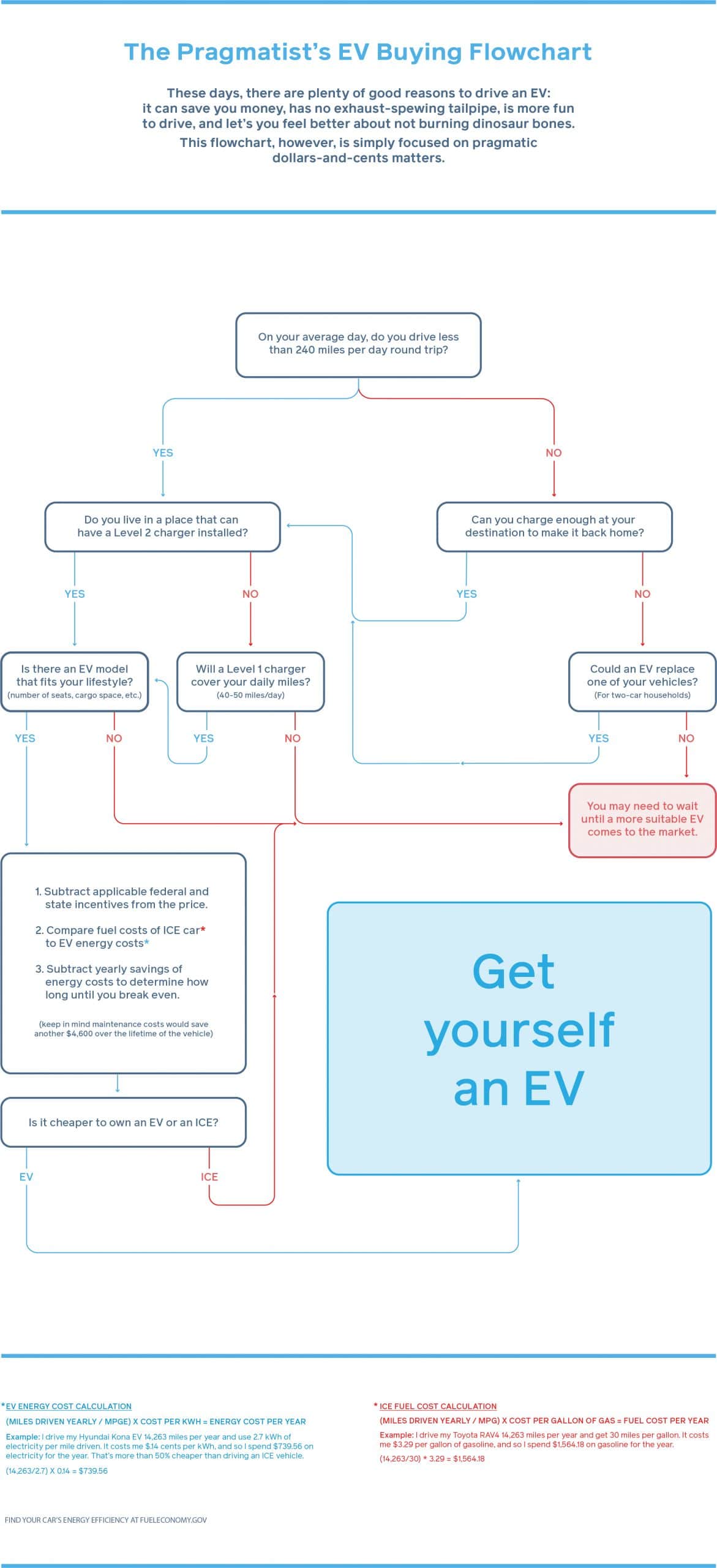

We’ve covered the main things you need to know to help you determine if you should purchase an EV or not. Now use this handy decision tree we made to determine if it makes sense for you.