How walkable is your town? If you live in the United States and answered “very,” you’re in a lucky minority. In a recent study of nearly 800 cities, North America ranked at the bottom in terms of “active mobility” modes such as walking and cycling.

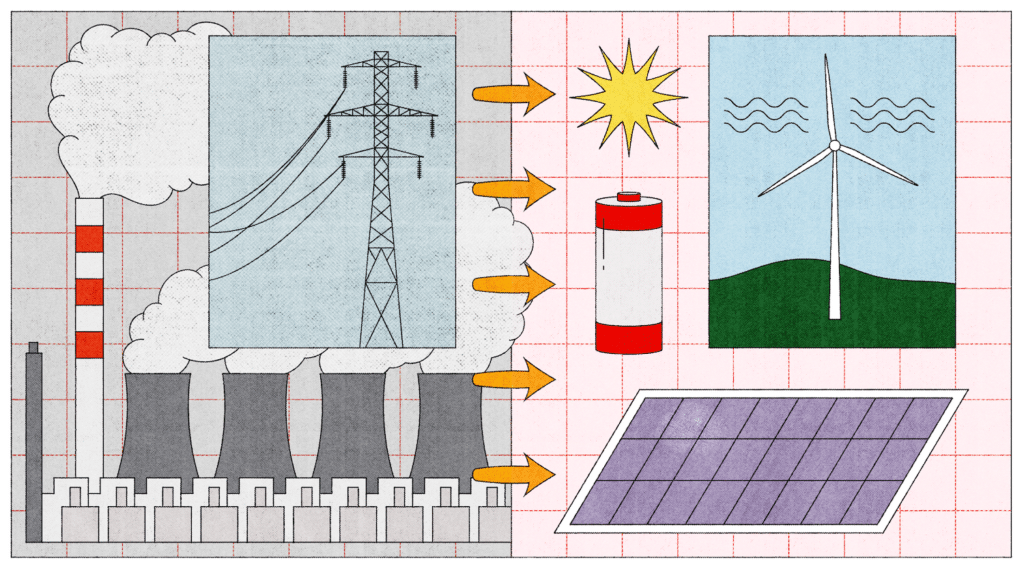

The problem with our over reliance on cars goes beyond the fact that road transport, a primary source of carbon emissions, is a climate hazard. Electric cars can help with that part, as well as the air pollution. But the traffic congestion, sedentary commutes, inequitable mobility, and other downsides of our national car glut are about sustainability in the broad sense of the word.

“Despite the burden of cars, policymakers still invest disproportionally in [motorized] infrastructure, inadvertently reinforcing incentives for their use,” the study authors write. But the researchers also documented lots of examples of places where life looks different, with pedestrian and cycling paths, urban green spaces, mixed-use development, and other approaches that have cut down on cars.

What does walkability mean?

The definition of walkability may seem self-evident: It’s the idea that you can get where you need to go on your own two feet. On websites such as WalkScore, you can plug in your zip code and see how your neighborhood ranks on a 100-point scale. Cities, of course, often lend themselves to walkability via population density: Manhattan gets a high WalkScore of 88.

But anyone who’s tried to walk somewhere in a car-centric suburb or a rundown neighborhood knows that walkability isn’t necessarily high just because amenities are nearby. Among walkability metrics focused on distance, “none provides a holistic examination of walking, which covers not just where you are going but also if your neighborhood is safe, equitable, and enjoyable to walk through,” a post at the nonprofit Urban Institute points out.

The institute’s analysis of Washington, D.C. incorporated not just access but also environment, policing, infrastructure, and safety. The northeastern part of D.C., the authors write, “have some of the worst-maintained sidewalks, limited access to key neighborhood destinations, high levels of police stops, and poor safety conditions.”

Another metric from the National Renewable Energy Laboratory, the Mobility Energy Productivity tool, considers commuter cost and the quality of what’s accessible—jobs and education, for example. The tool also attempts to answer how newer mobility modes like bike-sharing stand to affect an area, including how likely people are to use public transit.

The important point—and the great opportunity—behind these data tools is that they go beyond providing snapshots to people who are checking out a neighborhood. Granular, multilayered data can help policymakers and local agencies make investments where they are most needed, expanding walkability so that more of us can benefit.

The walkable city of Philadelphia, PA — Credit: Stephan Gladieu

Ways to Make Communities More Walkable

Many simple but powerful building blocks go into a walkable community, and any one of them can make an impact. Walkable cities in Europe and elsewhere offer models of how to get there.

Mixed-use development. Naturally, people don’t choose to embark on a traffic-filled, patience-busting maze just to go to work or get something to eat. They do it because they have to; most of us would rather be able to walk. Mixed-use development, which can combine commercial, residential, and retail space, cuts down on the need for driving to get things done. Such developments support the idea of a “15-minute city,” where most services are within a 15-minute walk or bicycle ride.

Safe sidewalks and streets. Vision Zero plans in Washington, D.C., and other cities across the U.S. aim to reduce fatalities partly by reducing traffic speeds. Another movement, Complete Streets, aims for broader inclusivity of travel modes, supporting pedestrians with enhancements like curb extensions, ample crosswalks, and accessible walk signals. Other approaches limit car access altogether, reorienting spaces toward pedestrians. Barcelona’s “superblock” strategy, detailed in this five-part series at Vox, creates zones where car access is limited and speeds kept at 10 kilometers (6.2 miles) per hour.

People-centered, visually engaging design. The choice between whether to walk or bike versus taking a car (if there is a choice) involves something more than just infrastructure and practicality. It’s about the walking experience: What do you see while you’re walking? How does it feel? Are there trees to shade your path, or maybe murals to beautify the scene? Small but important changes to a streetscape, such as landscape design, parks, and public squares, can make walking more appealing.

How to Get Involved

A common theme in many walkability success stories is a unifying, long-term plan. In Decatur, Georgia, three successive master plans helped transform the city into a more walkable place—a change informed by public opinion. Residents need to weigh in on decisions local leaders make about land use, transit corridors, and public spaces, not only making the case for healthier, more sustainable communities, but pointing out the economic benefit that can come from creating spaces where people want to live, work, and shop.

Consider following organizations such as America Walks and Smart Growth America, and look for local groups that also advocate for walk-friendly changes. And to learn more about specific ideas for walkability, check out the Pedestrians First campaign’s list of recommendations; the highlights at Walk Friendly Communities, which recognizes walkability initiatives and programs; and the National Association of Realtors’ advocacy guide, which is oriented toward realtors but has some good information, including cool renderings of possible improvements at specific locations.