The Cherokee Boys Club in Cherokee, North Carolina has had its electric school bus since early 2022. Everything’s going great: For summer school sessions, the bus did two routes per day on one charge, running clean and quiet. The interior is the same as a diesel bus, so the drivers feel at home.

Except… the hushed motor might be a double-edged sword for adults.

“That’s one thing about the electric bus, you can actually hear the kids talk about you,” said Donnie Owle, service manager for the nonprofit club, which runs all bus service for the Cherokee Central School System.

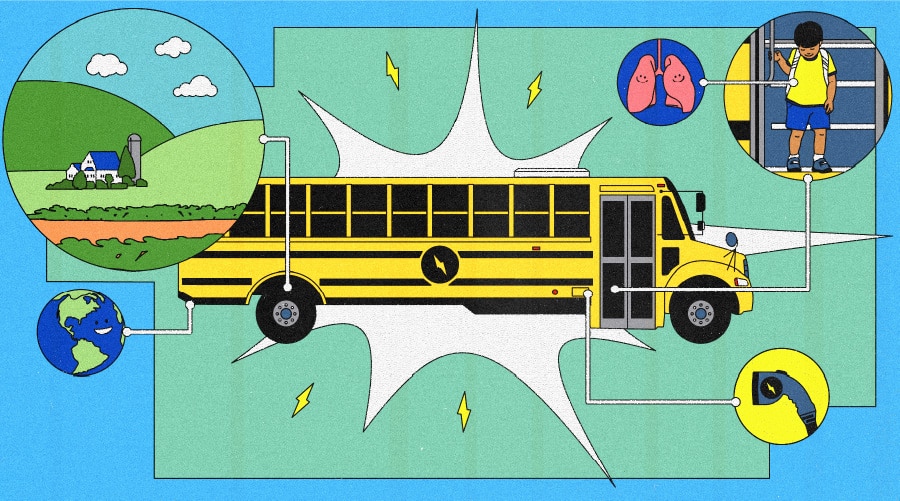

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ new electric bus is the first in North Carolina, but certainly not the last. So far, the state has awarded funding for six electric school buses to districts across the state, including the tribe’s, through its share of the Volkswagen settlement, which amounts to more than $90 million for projects that lower harmful carbon emissions and improve local air quality. Separately, the Cherokee Boys Club has ordered five additional electric buses, due at the end of 2022, and has applied to fund 14 more, which would make their fleet 100% electric. After that phase, they plan to take their commitment to clean energy to the next level by offsetting the electricity used to charge the buses by installing a solar bus depot canopy.

“We’re hoping to totally electrify the Boys Club school bus fleet,” said Katie Tiger, the tribe’s air quality program supervisor. A growing number of school districts are also recognizing that electric school buses are the way of the future because they help meet climate goals and cut airborne toxins, among other benefits.

In addition to the state funding, one of the country’s largest energy utilities, Duke Energy, has helped fund charging installation at the Cherokee Boys Club—originally founded in 1932 as a Boarding School and now a self-supporting Tribal Enterprise. The next four buses are paid for through a US Environmental Protection Agency grant, a fifth bus through the Boys Club itself. For the remaining 14 buses, the tribe is seeking federal funding through the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law.

Tiger had already been planning to seek funding for the first bus directly from the 2016 U.S. settlement with Volkswagen over the car company’s violation of tailpipe emissions requirements. But, she learned through the Land of Sky Clean Vehicles Coalition that the tribe could seek that money through North Carolina.

“We could have applied as a tribe and been a beneficiary,” Tiger said, but seeking funds through the state instead “was just a much easier process than applying to the Volkswagen settlement ourselves.” The bus was delivered in March 2022 during a ribbon-cutting ceremony where excited students got to take a ride and learn about the difference between electric and diesel models.

The Land of Sky Clean Vehicles Coalition had been following the Volkswagen settlement process, said Bill Eaker, a former coordinator (now retired) with the coalition who worked with the tribe on the grant. The coalition—part of the Land of Sky Regional Council—promotes the use of alternative fuels in the rural five-county area surrounding Asheville.

“Our job was to make sure that all our stakeholders’ fleets knew about these funding opportunities—especially this one, because it was so significant,” he said. “One of the goals of our coalition was to bring as much of that money back to our region as possible.”

The Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians has been proactive about alternative fuels: It began making its own biodiesel in 2012. Owle was open to the idea of an electric bus, but he had questions. In addition to making sure the Thomas Built bus had enough range to do its job efficiently, Owle wondered about how the bus would drive. Could it handle the Smoky Mountain region’s hilly terrain?

“It exceeded my expectations by 100 percent. The bus has plenty of power,” he said, adding that the bus doesn’t need charging between daily runs.

Eaker helped Tiger and Owle gather the information they needed to get funding and move ahead with the buses. The Land of Sky Clean Vehicles Coalition is part of the Department of Energy’s Clean Cities Coalition Network, which hosts regular events and offers a way for groups to share knowledge.

“One of the things we were hearing through the Clean Cities Network … was that it was critical for fleets that were looking at going electric—especially with medium and heavy-duty vehicles like buses—to start a dialogue with their utility very early in the process,” Eaker said. He encouraged the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians to engage with Duke Energy, which provided some funding and technical assistance on designing and installing chargers for the Cherokee Boys Club buses.

Tiger acknowledges that sometimes people are on the fence about something new. “We’re not saying it’s a fix-all for what our environment is going through. But we know that this is better locally, and it’s better for the kids. It provides a healthier riding environment to and from school,” she said. “That’s what’s important.”

The Cherokee Boys Club is also a service vendor for Thomas Built Buses, so Owle has trained technicians to work on the new school buses.

“America is going electric. It’s coming, no matter what,” he said. “With us being the forerunner, we’re ready for it.”