This article is from the May 26, 2021, issue of Flip the Script, a weekly newsletter moving you from climate stress to clean energy action. Sign up here to get it in your inbox (and share the link with a friend).

We talk a lot about the energy transition and the need to get to a future that doesn’t depend on fossil fuels. It’s an exciting prospect, and there are lots of steps we can take as individuals and as a society to get us closer to that goal—from switching to electric vehicles to putting solar panels on our roofs. But it’s also important to get clearer on what happens if we don’t take action, especially as the impacts of climate change become more immediate and more obvious. It turns out there’s a (not so) hidden cost to doing nothing—and fortunately, as a society, we’re getting a whole lot better at trying to measure it.

The costs of climate inaction

When we buy gas for our cars or heating oil for our homes, we’re used to just paying the price that’s been determined by the market, which shows up in the tally at the pump or on our monthly utility bills. But the wider costs of using those fossil fuels—to our climate, health, and society—aren’t factored into that price. Each year, the U.S. and other countries spend billions of dollars addressing (and trying to minimize) the damages from deadly wildfires, heatwaves, hurricanes, floods, and other climate-related disasters. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration estimates that in 2020 alone, the U.S. experienced 22 separate billion-dollar weather and climate disasters, well above the previous record of 16 annual events.

The wider costs of using those fossil fuels—to our climate, health, and society—aren’t factored into that price.

The health costs of climate inaction are equally mind-blowing. A group of doctors recently estimated the annual health impacts of climate change in the U.S. to be at least $820 billion, covering everything from treating asthma to fighting Lyme disease. But the actual price tag is likely far higher, given that we don’t even know all the impacts yet, much less how to calculate them. And the health consequences of climate change are expected to only worsen. According to one study, ongoing warming could raise the average mortality rate in Los Angeles by roughly 20 percent by the end of the century.

Baking climate costs into policy

Fortunately, we’re now seeing more aggressive action to tackle these hidden costs, especially at the federal level where it can make a huge difference. In February, the Biden administration agreed on a tentative new number for the “social cost of carbon”—essentially, putting a dollar amount on the impact every ton of carbon dioxide has on society and the environment. The new (tentative) figure is $51 per ton. This means that every time the government considers a project or purchase, this carbon cost now needs to be added to the calculus, potentially changing it dramatically. (The administration also estimated costs for two other greenhouse gases: methane and nitrous oxide.)

The logic behind the approach is simple: if policymakers have a better understanding of the actual societal costs associated with decisions that involve burning fossil fuels (like supporting a new coal power plant), then they might think differently about whether or not to pursue it (opting instead for a cheaper, cleaner choice like investing in solar or wind power). According to analysts, this type of carbon valuation could reshape some pretty significant decisions at the federal level, ranging from whether to allow new coal leasing on federal land, to determining what kind of steel or glass to use in infrastructure projects, to deciding which highways or pipelines can be built.

…If policymakers have a better understanding of the actual societal costs associated with decisions that involve burning fossil fuels (like supporting a new coal power plant), then they might think differently about whether or not to pursue it…

The idea of putting a price on carbon to inform federal decision-making first emerged during the presidency of George W. Bush, when a court determined that the administration’s mileage standards were illegal because they didn’t adequately consider the wider societal costs of vehicle emissions. President Obama set a price for the social cost of carbon at $37 per ton, but this was later slashed to near-zero under the Trump administration (which essentially ignored climate accounting in its rule-making). The new Biden administration estimate of $51 per ton is temporary and could ultimately reach $125 per ton once a more thorough analysis is completed sometime next year.

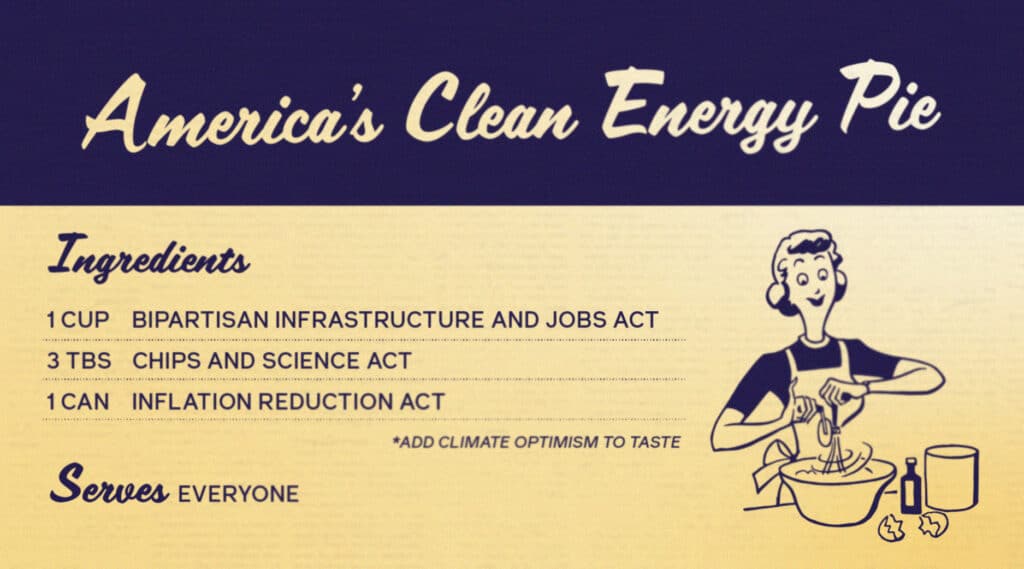

States and even cities have gotten in on the action. In December, New York adopted “value of carbon” guidance to help state decision-makers determine the climate impacts of proposed policies and programs going forward. Colorado, Minnesota, and Virginia all require regulators to consider the cost of climate damages when they evaluate new applications for power generation, and Illinois and Maine also incorporate such considerations into electricity-related policies. In Minnesota, the city of Minneapolis has set a $42 per ton value for the social cost of carbon and will apply it to policymaking.

Get over it

Not everyone is happy about putting a price on carbon. Some businesses worry that it will affect their bottom lines, since factoring in the climate impact could make their activities less economically viable. In particular, representatives of traditionally high-emitting industries, like chemical, energy, and cement companies, are eager to provide input on the new federal measure. Some conservative politicians have criticized the move as being “a backdoor carbon tax,” even though carbon pricing is where many countries are headed. Even supporters admit the measure isn’t perfect, as the estimated social cost of carbon could swing wildly between different administrations and is also sensitive to inflation.

But compared to the alternative (no valuation of impacts), it’s an important step. Despite the naysayers, many business groups have supported efforts to factor in the costs of emissions in federal and state decisions. Such a move sends a clear signal to businesses (as well as everyday Americans) that everything comes at a price—even inaction—and that the choices we make today can have big consequences down the line. Ricardo Lara, insurance commissioner for the state of California, has praised the Biden administration’s accounting approach because it allows elected officials to “measure climate risk in a way that people can actually understand, and in a way that can shape policy.”

As President Biden continues to prioritize considerations of climate risk throughout the government, his administration needs the right tools to help them make the best choices moving forward. The social cost of carbon is a critically important number, and it’s not the only number that matters. Other numbers, like the unprecedented level of public support behind clean energy (80-90%) and the percentage of emissions linked to consumer choices (55%)—numbers we can influence more directly—will also help shape the scope and speed of the transition to clean energy.