This article is from the April 21, 2021, issue of Flip the Script, a weekly newsletter moving you from climate stress to clean energy action. Sign up here to get it in your inbox (and share the link with a friend).

This Earth Day, things are looking a little more hopeful on the clean energy front, mostly because of promising trends in the political arena. But our work is cut out for us. The next ten years will be critical for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and making big moves toward a clean energy powered world. As the UN warned recently, the world’s climate goals currently aren’t nearly ambitious enough. Wildfires in California and the recent blackouts in Texas are just a few of the signs that things need to happen quickly and deeply. It’s time to engage in rapid, economy-wide mobilization, as we’re now in the Decade of Decarbonization.

While overall scope and ambition need to ratchet up, one key piece of this addressing this crisis will be cleaning up the U.S. power system. This is so critical because it presents an opportunity to decarbonize many other areas of our lives, as we move to “electrify everything” from how we heat and cool buildings to how we get around. President Biden, in his bold platform for economic recovery, has called for 100 percent clean electricity by 2035. That means getting to a zero-carbon grid in a mere 15 years. With a little lot of work, we’ve got a shot at making it happen.

Halfway to zero-carbon power

The good news is that, for this one piece of the climate solutions puzzle at least, we’re already halfway there. A new report from Lawrence Berkeley National Lab (LBNL) notes that carbon dioxide emissions from U.S. power plants in 2020 were half (52 percent) of what experts predicted they would be 15 years ago. Of course, COVID helped put a damper on last year’s emissions, but even if you use 2019 as the end year, emissions were still 46 percent below the 2005 projection. This happened even without all-hands-on-deck action, suggesting that with a more dedicated focus in the coming years, reductions can happen even faster.

A key caveat is that a big contributor to the drop in power sector emissions since 2005 was the shift from coal to (relatively cleaner) natural gas generation—a “decarbonization windfall” that can’t really be repeated since we’ve already picked that low-hanging fruit. Fortunately, there are other important ways to get to zero-carbon electricity. Here’s a (quasi) roadmap for action in five key areas:

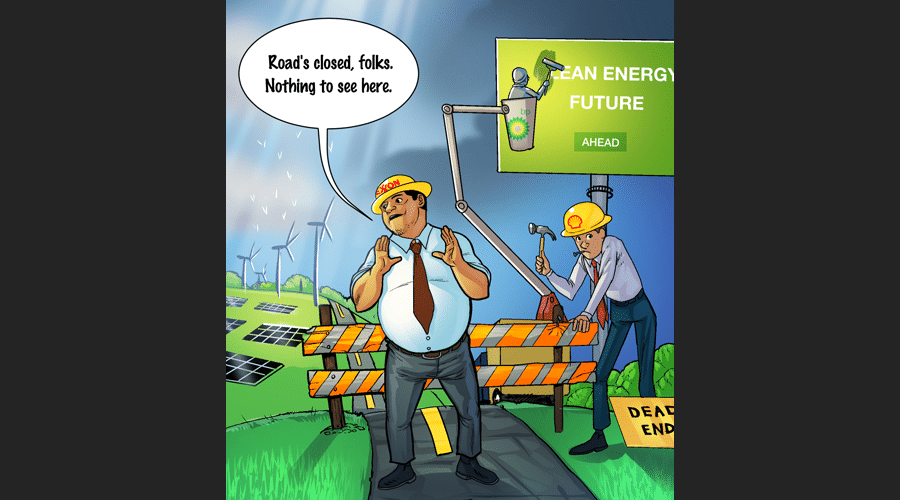

1. Way less fossil fuels, way more renewables

Maybe the most obvious (but most important) route is reshaping our mix of power sources. This would mean continuing to retire polluting coal plants (already well on the decline) and ramping up investments in renewable energy, especially over the next five years. It also means putting the kibosh on new gas-fired plants (which, although lower-emitting, still contribute to the climate problem). But we can’t just get rid of fossil-based power generation without replacing it with something else that’s as competitive and reliable. That’s why we need to go big on wind and solar, as well as energy storage to ensure an uninterrupted power supply for those times when renewables aren’t producing.

By one estimate, getting to a carbon-free grid by 2035 could require installing an average of 70 gigawatts of new renewable capacity annually over the next 15 years. It sounds daunting, but given recent trends we can be cautiously optimistic. Wind and solar capacity grew an average of 17 gigawatts between 2017 and 2018, but by 2020 (just two years later), this annual growth figure had doubled to 34 gigawatts. It basically needs to double again. With the growth in renewables well exceeding forecasts in recent years, it could continue to do so.

2. Bigger, smarter electricity grid

According to estimates, more than half of the wind and solar capacity needed is already in the pipeline (including current wind, solar, and storage projects). But it can’t all be built without expanding transmission capacity—such as adding power lines—and improving grid operations to better support the integration of renewables. In addition to the general rise in electricity demand, the grid will need to be able to accommodate the extra growth in load from the increased electrification of buildings and vehicles (projected to represent 2-3 percent annual growth over the coming decade).

These grid improvements will need to occur alongside infrastructure ones to get to 100 percent electric vehicles (EVs), including major investments in charging and grid upgrades to serve EVs—estimated to cost a combined $10 billion per year by 2035. In total, President Biden’s plan has called for a $2 trillion investment in clean energy and infrastructure.

3. Strong policy support at all levels

A zero-carbon grid also won’t happen without strong clean energy policies, at all levels of government. Evergreen Action, in its Roadmap to 100% Clean Electricity by 2035, has urged Congress to do whatever it takes (eliminating the Senate filibuster, using budget reconciliation, etc.) to pass a federal Clean Electricity Standard. This would require utilities to increase their use of renewable or carbon-free energy resources in electricity generation, and has proven among the most effective state and local policies to reduce carbon emissions. More than two-thirds of voters support such policies.

Here again, policy action in the power sector needs to go hand-in-hand with a nationwide policy push to support 100 percent electric vehicles by 2035. A rapid EV rollout would have huge carbon, health and jobs benefits, contributing to an estimated 45 percent reduction in economy-wide greenhouse gas emissions through 2030.

4. Bring everybody—including utilities—to the table

Corporations are already playing a big role in the shift to clean electricity through their buying of renewable power, and automakers like GM are making commitments to sell only EVs by 2035. On the consumer side, support for clean energy is high, and there’s rising interest in both rooftop solar and EVs. But ultimately, utilities will be the key players in the shift to 100 percent clean electricity.

Most U.S. utilities’ processes for deciding how to generate their electricity are outdated, favoring “legacy technologies” like coal and natural gas, and they don’t provide a level playing field for renewable energy generation. Over the coming decade, utility investments will need to be aligned with clean energy goals to avoid locking in billions of tons of CO2 emissions and setting back progress on climate. Researchers with RMI recommend that utilities adopt next-generation procurement practices that promote fair competition between different energy sources (including small-scale renewables) and focus on objectives like resilience, decarbonization, and local economic development. By carefully managing the shift to clean electricity, utilities can simultaneously lower electricity bills, cut carbon emissions, and retain reliability.

5. Consider justice and equity angles

Finally, achieving rapid 100% clean power will require policies that are justice-centered. This includes, for example, designing a Clean Electricity Standard that not only rapidly decarbonizes the power sector, but focuses on equity, good jobs, and community benefits while doing so. EV policies also can be designed to share EV benefits more equally, such as by supporting charging infrastructure in low-income communities or providing point-of-sale rebates to help lower-income buyers. Biden’s plan for 100% clean electricity includes deep commitments to confronting systemic environmental injustice.

Let’s. Get. Going.

Of course, 100 percent clean power isn’t the only solution to addressing the climate crisis—but it’s a big one. We need to go all-in on a clean energy transformation, including harnessing the opportunities of explosive tech growth in both the power and transport sectors. As an author of the LBNL report observed, the U.S. was able to get “halfway to zero” over the past 15 years without really trying very hard, but we still succeeded. The choice now, he says, is “between muddling along as in the past or making a consistent and long-term push.” Let’s opt for the latter.